New Heart, Old Soul Ready to RiiSE? An innovative Vancouver company will convert your beloved sport or classic car to electric for a cleaner and greener future.

by Kara Cunnigham

RiiSE EV founder and CEO Dean Kneider is doing something special. He and his partners have recognized a timely niche in the rapidly evolving world of electric vehicle (EV) transportation, and they are breaking new ground in Canada. Their Vancouver-based company, RiiSE EV, retrofits gas-powered vehicles into electric ones. The company name, RiiSE, stands for “The Realization of Innovative and Integrated Sustainable Energy.”

Kneider’s journey into EV tech began about eight years ago when he bought a hybrid vehicle and started researching electric cars. Four years later, he found a company in the U.S. that was doing electric conversions, but it had a three-year wait period. He did not want to wait that long, and he also had friends who wanted to convert their cars: “I just started researching, and soon I had a pile of papers on it stacked up like the Rocky Mountains,” he said.

Kneider quickly realized that with all his connections, skills, and other know-how, he could get a conversion done a lot quicker. He was also inspired by his son and a desire to lead sustainable economic and environmental change for subsequent generations.

"Another thing about classic cars is that they are really good cars. They were built to last. Today cars are being built to be fixed.”

Collision Quarterly had the pleasure of sitting down with Kneider to discuss his passion for cars, greener transportation, and finding scalable and economically viable EV conversion solutions. A conversation with Kneider is an education for any automotive enthusiast with a beat on the future.

Collision Quarterly (CQ): Why would someone want to convert their classic car?

Dean Kneider (DK): Let’s say your grandfather left you an old ‘64 Mustang, but it needs repairs. Now I can tell you, my children and your children would love the car. They would want to fix it. But with all the electrification out there, the next generation who is gifted old cars, they will probably want to electrify them more and more.

CQ: Why do you choose older cars?

DK: I chose older cars because they’re easier to work on because anything post 1986 has CAN Bus systems, which are all the computers that run a car. Now the cars I buy, like the 1970s Porsches, they’re just straight engine, there’s no electronics. They are pretty basic. So you are just taking that one engine and putting in an electric motor.

Another thing about classic cars is that they are really good cars. They were built to last. Today cars are being built to be fixed. The old Mercedes, the old Porsches, they’re still around today because they were built well. They were built with the right steel, the right frames, and the right components. There are many vehicles manufactured out there that are not going to last more than 20 years. Their frames are rusting out because they weren’t built to last.

CQ: Is converting a vehicle affordable for the average person?

DK: Eventually it will be, but 45% of the overall cost is battery technology right now. The controllers, the battery management systems, the wiring looms, and everything else that goes into it, is going to be pretty standard.

When we started out, it was costing us $60,000-$80,000 to do a conversion, but our company’s goal is to get the cost down to $49,900 for a full conversion. The price will go lower as we buy more volume, but you can only do this with certain cars. When somebody asks me about converting their vehicle, I ask two questions: 1) How fast do you want to go (which helps me dictate the type of motor that I’d put in the car); and 2) How far do you want to go (which dictates how many kilowatt hours that I put into a car to give you distance and range). All this can vary, and there are choices to make.

CQ: Why should the average consumer consider converting their vehicle, classic or not?

DK: Here are the economics for you. If you take the 2000 Caravan or Astro van or minivan, it’s probably only worth $8,000. Why would you spend $50,000 converting it? That’s why we convert old, classic cars worth $50,000-$100,000 or more. The problems come with getting parts for their engine. You drive it for a weekend, and then you put it in the shop because it’s leaking oil. But where the metrics come is if you take the average husband or wife that has a minivan, and it’s costing them on average probably $100 to $120 to fill the tank, and let’s just say it’s $100 every week, that’s $4,000-$5,000 a year just for gas.

Generally you might have $1,000 or $2,000 worth of maintenance to do a year, and then you’ve got your winter tires or your summer tires, windshield wipers, or whatever else. So you’re kind of in the range of about $8,000 to $10,000 a year to operate a car. So when I go down the path of where the value comes, at some point the inflection point becomes I would like to do right for the planet, and I don’t have to throw away the car.

"There are billions of cars on this planet. We don't need to keep being a throwaway society, and people are going to want to keep their classic cars on the road.”

If it’s costing you $10,000 a year to operate your car, in four to five years, in the best-case scenario (as your daily driver), it has paid itself off. And that’s what I’ve tried to do with these electric quotations is make them a daily driver. So if I converted a car, and I drive it every day, and it costs me $1.22 to charge every night, this will cost me about $40 a month at the most. That is what my electrical bill is, and I drive the car for $40 a month instead of $400.

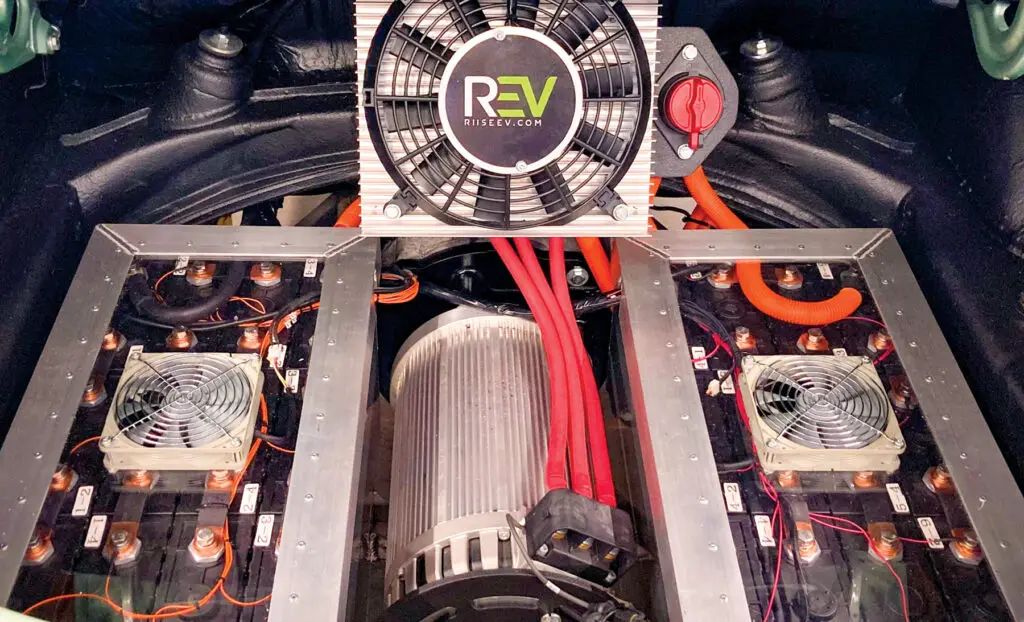

Also, so much of the automotive industry is in the parts. To look after a 1970s engine, it’s hard to find all those parts. So you have to remember that my electric motor has 20 parts inside of it. The engine I took out of my Porsche had 2,200 parts. So there is very little maintenance on an electric engine.

CQ: How many conversions can you do a year now?

DK: The goal would be to do 24, and I’m trying to do what I call a platform. The reason I chose the Porsche series is that they made that Porsche body style from 1968 to 1996, and up to ‘86, there were no CAN Bus systems in them, so the 1968 to 1986 models are easy to work on. So there are hundreds of thousands of those cars out there, and I’ve made two different types of kits where I can now duplicate them, meaning I can build the battery boxes, put all the stuff together, send it to somebody in Australia, and they can put it in their car for all intents and purposes.

CQ: How long does a conversion take?

DK: The first prototype I built took us three months, but I probably could have done it in a month and a half. I learned a lot building the boxes and other stuff. Custom cars can take six months, but our company goal is to charge $49,900 all in and have you in and out in a month (or less).

CQ: How do you find the skilled labour necessary for this kind of work?

DK: Generally I look at people who’ve got an electrical background and a love of cars. There aren’t a lot of people who do this yet, but there will be more and more through creating opportunities. There is nowhere I can go to hire people right out of the gate.

There are educational institutions such as BCIT (British Columbia Institute of Technology) and other organizations in British Columbia that train people to work on EVs, but they generally only teach OEM. The only certification you can get when you go to places like BCIT or Kwantlen, or any one of them is a Red Seal certificate to become a Red Seal electrician or mechanic. Tesla hired BCIT to teach all their EV courses, but they have no independent certification. You can’t learn how to be an independent mechanic on electric vehicles anywhere yet, but it will come.

When you get an electric car, right now they all have to be sent back to their OEMs for maintenance and repair because there aren’t any independent mechanic shops. When you put a computer in a car, it might have a program for Tesla, but that won’t work with the Kia Soul, and it won’t work with any other electric car or the Ford hybrid either.

CQ: Do vehicles need any body modification or structural work to accommodate the battery or motor?

DK: You have to look at your gross overall weight. If that’s going to change, then you have to do a modification. I try and stay within that range of the vehicle.

With the Porsche, for example, I took out the gas tank in the front of the car (the engine is in the rear on a Porsche). Now, removing that tank changed the vehicle’s weight, so I put six of my 10 batteries up there, so I kept the weight distribution of the car the same, and I did not have to do any modifications outside of that. The only holes I had to drill were to hold the battery box. Everything I do is about safety. Safety is the most important part because the car is going on the road.

Think back to your dad or your brother. You know, when they got a car or that truck, and they blew their inline-six engine and they put in a V8? It’s been happening for years. The challenge is, if the V8 in that car was originally built with an inline six, and it was crash tested with an inline six, the firewall is only built to withstand an inline six. And if your dad put a V8 that weighs 200-400 pounds more, nobody ever looked at any of that stuff. The only people that look at stuff like that are the lawyers when the vehicle gets into a car wreck.

There are hundreds and thousands of cars out there with V8 engines that were never born with a V8 engine in it, right? I try to keep the electric motors and the weight as close to pound-for-pound the same.

CQ: Are there any OEMs interested in electric conversions with their classics?

DK: You know what is interesting? Companies like Mini. If you have one of the old 1960 or 1970s Minis, you can send it back to the UK, and they will now electrify it. The OEMs should be looking at this. Toyota is getting into it. There was an article in the paper just the other day. The old Datsun, for example, Toyota is converting them. I will start coming up with kits for their old cars because I think people are just realizing that there’s so much equipment, so much material already on this planet for cars. And the same with buses. That’s a whole other animal.

CQ: What are your biggest obstacles right now?

DK: The biggest obstacles as a company is raising money to expand because scale is what brings the price down. If I can order all my components and have 10 kits sitting every month, then I’m not paying exorbitant prices for the supply chain. Batteries are 45% of our overall cost, and so I work with different batteries and battery systems, between air cooled or liquid cooled.

Everything costs money, but I want to show people that this is economical, and it is profitable, and if I make money doing this, I’m not going to be upset by it because I think I’m doing the right for the environment. Profit is not a dirty word. You just have to want to do it right. What throws this business off are the challenges between the supply chain and scalability. It was harder two years ago, but it is getting easier now.

"There are billions of cars on this planet. We don't need to keep being a throwaway society, and people are going to want to keep their classic cars on the road.”

CQ: How do traditional automotive enthusiasts respond to your classic car conversions?

DK: I don’t touch the hot rodders—they love their chrome engines, the sound and gurgle and smell of the old leaded gasoline and stuff. With EV conversions, this is a movement. If your father left you his 1964 Mustang, you’re probably driving it as a Mustang with the V8 or the inline six or whatever was in it. But when you give it to your kids, they may have to make that change. It is a slow adoption.

I’ve been to a bunch of Porsche club meetings and Porsche was always known as an air-cooled car. I have air-cooled batteries in one, and I have liquid cooled batteries in another, so I took an air-cooled car and made it a liquid cool. Now there are traditionalists who do not like it. Some people just don’t like change. But to make this 1976 Porsche a daily driver with no faults, no repair time, no down time, and I can basically drive it every single day for $1.20 of electricity a night? Think about it.

CQ: Are there a lot of recyclers with the right inventory for EV conversions, or do you have to buy new?

DK: It’s just a handful in Canada. There are companies that are doing it on scale because this is what their business is. They look for used electric vehicles and take all the parts because there’s a lot of people starting to pop up, like the hobbyists. There are people who have got the Nissan Leafs, for example, and they want better batteries.

CQ: Do you ever require collision repair or refinished services for these cars?

DK: If you get in an accident, and you’ve written off the front end of your car and your engine is gone, but you love the car, and it was your dad’s 64 Mustang, you will want to get it repaired. So now you have to make a decision. Are you going to put a new engine in it? Or are you going to put in an electric motor? But when you bring it to us, I want it EV ready. Meaning the car needs to be exactly the way you want it as is, you’ve just blown the engine.

We are not a repair shop, but I need the repair shops to look after these cars because when people have blown their motor, you can generally buy a used motor for a car for five to 10 grand, and then it’s $2,000 to $3,000 to put it in, so you are in $13,000. For an Audi or a new Mercedes, or something like that, you could be in upwards of $30,000-$40,000.

You can still buy a used Nissan Leaf or a Kia Soul for $28,000. You get the full brand-new car. It’s only five years old, so why would you convert? So that’s why classic cars make sense.

CQ: How do you see EV transportation, technology, and conversions evolving?

DK: I’m not revolutionizing anything, this has been around for a while, but I am trying to commercialize it so people can take advantage of EV conversions based on scalability. The savvy people, the frugal people, the visionary people, the thinking people, the where do we want to be people—they are making this happen. It is a movement, and it is a good thing. It’s all part and parcel, just as long as you’re getting rid of fossil fuel burning.

Now lithium ion or lithium phosphate, they’re not the greatest for the environment. So the battery section will eventually change as well, but we’re making steps in the right direction. At the end of the day, we’re doing the right thing.

People get very enamored with all the new stuff out there. Everyone loves Elon Musk. Everyone loves Rivian, Canoo, Lucid, all the brand-new cool cars, and they still talk about the Nissan Leaf and the Kia Soul. But what I’m doing is preserving the past. I’m preserving the future by converting the past. There are billions of cars on this planet. We don’t need to keep being a throwaway society, and people are going to want to keep their classic cars on the road. We’re here to provide logical steps toward greener transportation.

Collision Quarterly would like to thank RiiSE EV founder and CEO Dean Kneider for taking the time to share his passion and vision with our readers. To learn more, visit riiseev.com.